The Unchecked Authority Always Falls: Napoleon’s Cold Retreat from Moscow

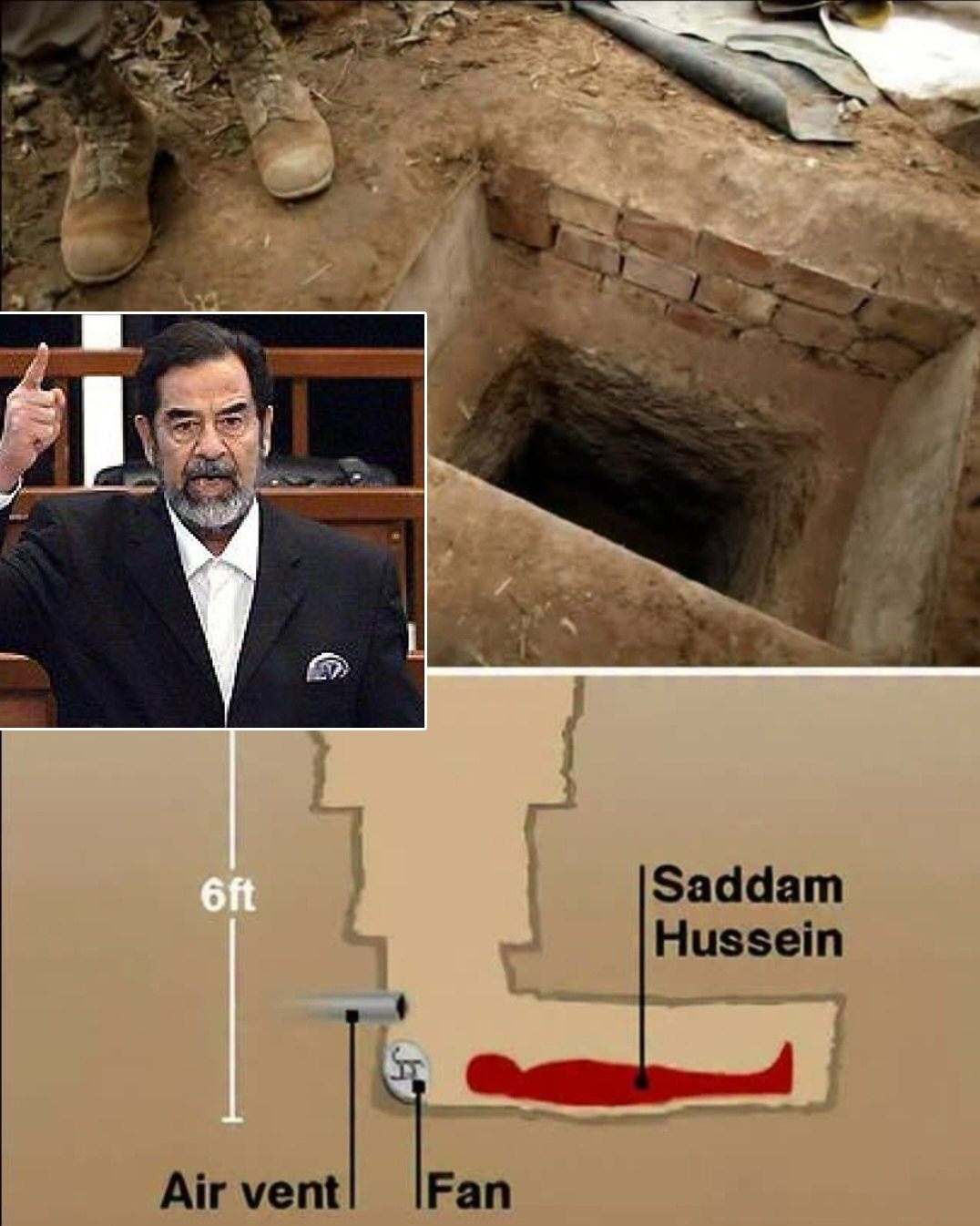

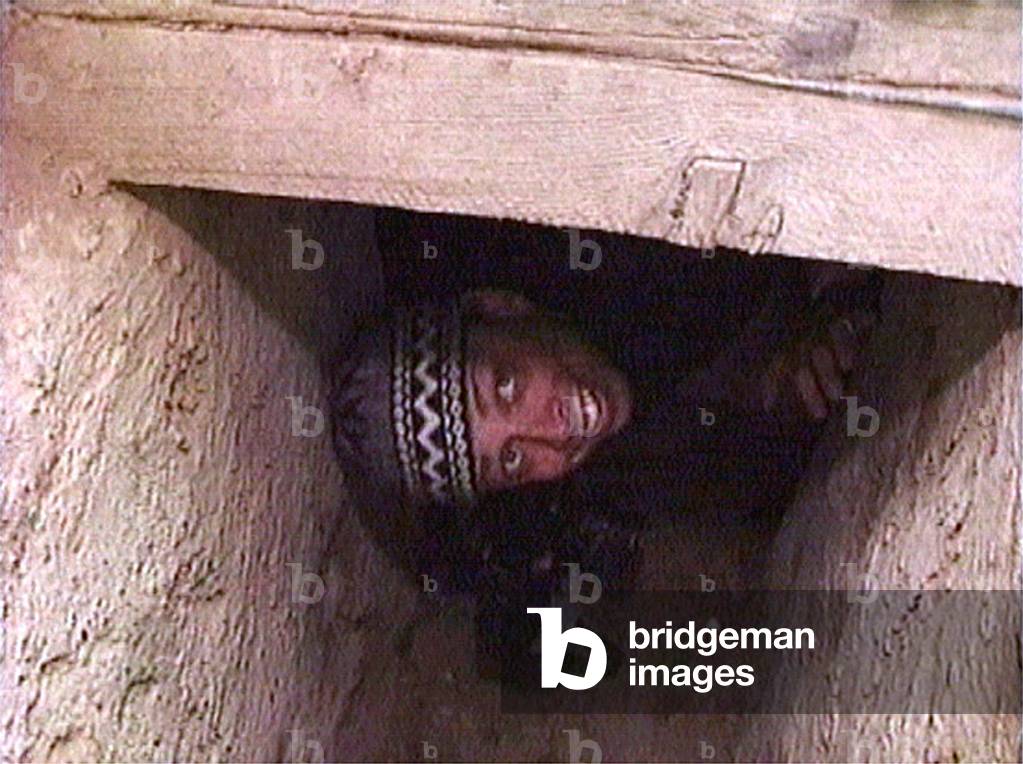

The image of Saddam Hussein, the former master of Iraq, dragged from a cramped, dirt-filled hole is a modern and stark reminder: no tyrant’s power is absolute, and every immense authority is ultimately checked by reality. But history is replete with these chilling anti-climaxes, perhaps none more spectacular and devastating than the downfall of a man who crowned himself Emperor of Europe: Napoleon Bonaparte.

In 1812, Napoleon stood at the pinnacle of his glory. His Grande Armée—a staggering force of over 600,000 men drawn from across Europe—marched into Russia, intending to humble Tsar Alexander I and complete his dominance of the continent. The weight of his power was unmatched; he controlled kingdoms, reshaped borders, and had brought the entire French nation into a fever pitch of imperial ambition.

The Hubris of the Crown

Napoleon’s hubris was total. He saw himself as the logical successor to the Roman emperors, an unassailable conqueror whose will alone could dictate the fate of nations. He ignored the dire warnings about the Russian terrain and the coming winter, confident that a swift, decisive battle would force the Tsar to surrender.

But the Russian campaign became his undoing—a perfect, terrible illustration of how unchecked ambition meets its natural, humble end.

The Russians refused to fight him on his terms, instead employing a scorched-earth strategy that led the French deeper and deeper into a desolate landscape. When Napoleon finally took Moscow, he found not a conquering prize, but a city deliberately emptied and then set ablaze by its own people. He occupied an empty shell, surrounded by the silence of a ruin.

The Retreat: From Emperor to Survivor

The true moment of collapse was the infamous retreat. As winter descended with a fury the French were unprepared for, the Grande Armée did not retreat; it disintegrated. The cold—“General Winter,” as it was called—proved a far more formidable enemy than any coalition of European armies.

The great Emperor, who had ridden into Russia with legions and glory, now fled on a sleigh, leaving his army to a harrowing death. The soldiers, once proud conquerors, became ragged, frostbitten figures, forced to eat their dead horses or resort to cannibalism just to survive. The weight of their packs, filled with plunder, was exchanged for the terrifying, singular weight of survival.

Of the over 600,000 men who marched into Russia, perhaps fewer than 100,000 returned alive. The military might that symbolized Napoleon’s absolute authority was reduced to a scattered, pathetic mess of survivors, all because the Emperor’s will was powerless against the simple, indifferent elements of nature—the cold, the snow, and the hunger.

Napoleon’s eventual exile to tiny islands was a physical echo of this defeat, but the psychological and historical lesson was already complete: like Saddam Hussein in his cramped pit, the man who sought to rule the world was utterly humbled by a force he had overlooked—the brutal, basic reality of the earth. The cold retreat from Moscow remains one of history’s clearest, most devastating images that the pursuit of unchecked authority always ends in the cold, inevitable fall.